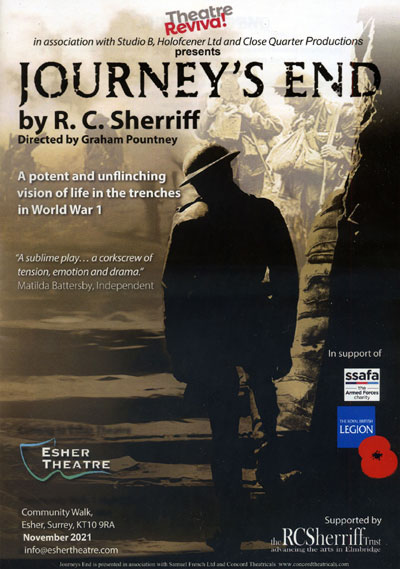

On Thursday November 11th I had the great pleasure of accompanying my lovely wife Diana to the Esher Theatre, for the most appropriately scheduled premiere of a short run of R.C. Sherriff's "Journey's End". Neither of us had been to the theatre in years (and haven't been out much at all since 2019 of course), which added an extra frisson of excitement. The theatre turned out to be a modestly sized venue with uncomfortably tiny chairs, but with the undeniable blessing of a well-stocked bar and the unexpected freedom to take drinks into the auditorium! Our seats were right in the front row, giving us an exceptionally clear view of the proceedings - perhaps too clear, as (there being no stage curtain) we could see the scene-shifting going on under cover of darkness. :)

Stage design was traditional for Sherriff's play, presenting us with the interior of a (rather generously proportioned) British company command dugout on the Western Front in March 1918. It stood up very well to close inspection - I spotted some lovely original artefacts including a folding camp bed just like one I once slept on at a reenactment event. A short set of steps in the rear wall opened on the partially visible trench beyond, which was used highly effectively during the periods of high activity associated with the raid and concluding German offensive. Briefly visible figures, voices off and judicious sound effects created a most convincing impression that we were indeed in the second line of an actively held trench system. The sight of stretcher bearers hurrying by (and venturing into the dugout itself near the end) was particularly impressive and moving. Uniforms and equipment generally looked splendid (albeit rather clean!), and everyone seen on stage came across as knowing their business and the use of their kit. This is not an easy thing to achieve, but makes a striking difference even to the non-specialist eye. I am given to understand that this was thanks to the efforts of Khaki Devil, a name familiar to me from living history circles, and can well imagine that a great deal of work and attention to detail went into it.

As some of you will know, the play has a special significance for my family. Sherriff was inspired by his own service as a subaltern with the 9th Battalion / East Surrey Regiment (72nd Bde. / 24th Div.), the same unit as my father's great-uncle Charlie Woodbury; hence my father's study of the "Journey's End Battalion", including many published articles and two books to date (and in turn, my own introduction to the rigours of WW1 research for publication). Like Sherriff, great-uncle Charlie did not escape the war unscathed physically or psychologically; unlike the playwright, he was unable to readjust to civilian life and led a troubled life foreshortened by alcohol. This was also the case to an extent with Captain Godfrey Warre-Dymond, generally acknowledged as the main model for Stanhope in "Journey's End". Although a much-admired and decorated company commander who withstood the worst the war could throw at him, Warre-Dymond likewise struggled with drinking, a messy divorce and bankruptcy after returning to civilian life. He had been Sherriff's hero as his immediate superior, but by the time he came to write his play in the 1920s Sherriff was clearly just as aware of Warre-Dymond's human fragility as of his own - which is itself incarnated in the play both as the naive Raleigh and (less flatteringly) the broken Hibbert. Sherriff's letters from the front show that he constantly struggled with his nerves, and was haunted by the fear of breaking down and failing in his responsibilities as an officer.

This is my long-winded way of getting to the point of the play, which is all about individuals struggling separately with the intolerable psychological burden of industrialised trench warfare and their individual responsibilities within its massive organisational machinery. Most realistically, lethal violence happens suddenly and randomly (and off-stage). No-one is irreplaceable or invulnerable, and the veteran survivor and hapless newcomer alike can die suddenly and meaninglessly. These terrible moments are interspersed with long periods of agonised waiting, which is where the focus of "Journey's End" actually lies. The play is infused with a very authentic sense of desperate humour, with the casual witticisms of Captain Hardy and the clowning of Mason the cook raising many chuckles in the audience early on. As the play progresses, we see this brittle jollity fracturing under the weight of personal tragedy and the approach of mass slaughter in the anticipated German offensive. Just as the playwright intended, the periodic audience chuckles died out in the second half. By the end, almost every major character's true feelings about the grim situation are exposed - there are no more jokes, no more whisky and no more time to put off the inevitable.

Above: Diana's crafty photo of the stage just before the opening of the play.

The cast all inhabited their parts very convincingly, and it is challenging to assign individual praise without having to run through the list one by one in the interests of fairness. Mention must of course be made of Alex Mircica in the lead role of Captain Stanhope, a part given in the original West End production to Sir Laurence Olivier (who admired the play but felt that he had not done justice to the role). There is no doubt that a performance of this play lives or dies by the effectiveness of its Stanhope, since all the other characters are largely defined by their relation to him and are constantly reacting to him. Alex plays the part with great conviction and energy, making the character's great strength as a painfully conscientious leader of men as well as his profound depths of alcoholic despair and self-loathing equally believable. His presence is always accompanied by a palpable tension, which can and does boil over under provocation into a terrifying volcanic rage; the subtler notes of genuine friendship and affection are also struck with a very real human warmth. Around this strong core, director Graham Pountney has assembled an excellent ensemble cast. I really must mention Ray Murphy as Lieutenant Osborne, a creditably unassuming tower of quiet strength who excels in the personal scenes with Stanhope and Raleigh. Kieran Seabrook-France as 2nd Lieutenant Raleigh is just as painfully boyish as he should be, wearing his heart on his sleeve and appearing genuinely traumatised when exposed to death at the front and its cold aftermath. Gregory A Smith as 2nd Lieutenant Hibbert deserves great credit for making his broken and desperate character sympathetic, and is truly impressive in his most spectacular scene with Stanhope. Brendan Quinn as 2nd Lieutenant Trotter should certainly not be forgotten either, making his character much more than mere comic relief. Trotter gets a few lines to hint at the depth of his own feelings, and they are delivered most tellingly; the man who is supposedly invulnerable to the strain due to 'lack of imagination' still cares and still feels the gravity of the situation. When the situation turns deadly serious he is suddenly all business.

I could go on, but at this point I really should be wrapping up... my apologies to those I have not mentioned by name. Suffice to say, the play concluded in the traditional manner as per Sherriff's original staging. The cast did not return to the stage - leaving us in sudden, silent contemplation as the ending sank in. Instead they were gathered outside, lining the path in front of the theatre as we emerged. This was highly affecting, though by the time we left the bar the fourth wall had broken down and we found ourselves enjoying a brief but pleasant chat with the leading man.

To summarise, this was an excellent and sensitive production of a perennial classic. It was also a splendid evening out, and we warmly recommend the Esher Theatre as a venue (with a minor caveat for the uncomfortable chairs!). Should the production be revived again, I strongly suggest that you seek it out!