(Note: this review is based on an advance copy which only extends as far as summer 1916, just before the departure of the diarist's unit for the Eastern Front)

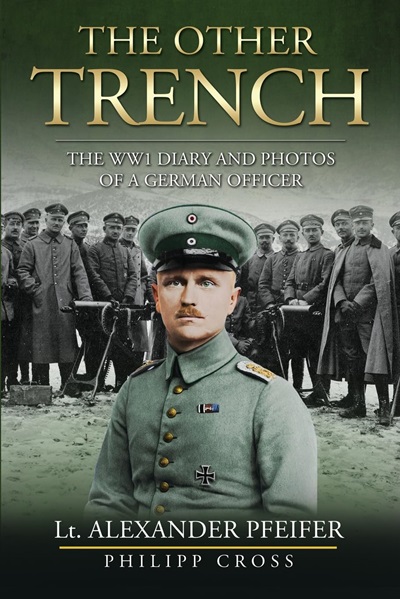

Many of us come to the study of the Great War through genealogy, and Philipp Cross is no exception. Raised as a fully bilingual Anglo-German, he has done us the great service of translating and extensively annotating his great-great-grandfather Leutnant der Landwehr Alexander Pfeifer's wartime private diary for publication. It is unquestionably an historically valuable document from a highly interesting subject - Pfeifer was a platoon and later company commander, close to the 'sharp end' but still high enough in the command chain to be mentioned in his unit's published history and to make decisions of real tactical significance. Furthermore his unit, Kurhessisches Jäger-Bataillon Nr. 11, was a formidable one which saw a great deal of action - not only on the Western but also on the Eastern and Italian fronts. From July 1916 it was part of the 'all-Jäger' 200. Infanterie-Division, rated in 1917 by the British as "one of the best divisions in the German Army". For British readers, another major draw will undoubtedly be the eyewitness accounts of fighting against the BEF near Neuve Chapelle in 1914-1915 and at the infamous Battle of Loos in September 1915.

Like many of his contemporaries, when mobilisation was announced Alexander Pfeifer made a deliberate plan to record his experiences daily for the duration. Although there are inevitably many gaps (either when very little was happening, or when too much was happening and he had to catch up later), Alexander continued to write his diary throughout the war and to post it home piecemeal for preservation. He states that he declined to edit anything when typing up his notes post-war for posterity (which he assumed would consist solely of future generations of his own family) - "I have intentionally changed nothing, as these reports are intended to reflect my true feelings at the time."

The result certainly has all the authentic rawness and immediacy one would expect of such an account, constantly immersed in the problems of the moment - frequently mundane, occasionally humorous and periodically terrifying and horrific. Alexander's descriptions of the fighting are chaotic and brutal, with certain scenes of death and mutilation depicted with such appallingly vivid intensity that they must have been traumatically seared into his mind's eye. He is equally frank in describing the routine misery of the trenches, but is never self-pitying or didactically hostile to the war itself - we are simply shown his current situation and how he and his unit have adapted to it. He attempts to maintain an impersonal journalistic tone, commenting only briefly on his relationships with specific colleagues, subordinates and superiors; home leave is marked but not described at all. This makes the occasional flashes of strong emotion which we do see particularly potent. His experience of Christmas 1914 is strikingly bleak - although within miles of well-documented scenes of fraternisation, his unit had recently been through brutal fighting against Indian troops and spent a wary and miserable Christmas in the front line.

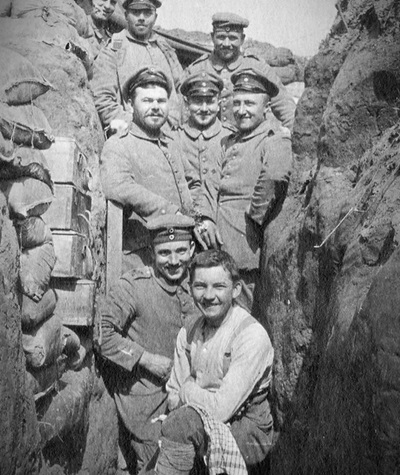

In addition to his diary, Alexander took or acquired hundreds of photos which start to fill the text from spring 1915 onwards. Like most of his contemporaries, he seems to have begun documenting his war experiences in this way after the onset of trench warfare - and indeed, after the first winter. Undeterred by official disapproval of cameras being taken into the trenches, the photographic coverage extends right into the front line - or even beyond, as there are several shots of distant enemy positions taken 'over the top'! For a German officer it was surprisingly easy to get away with such irregular photography, though less so later in the war.

Most remarkably Alexander's legacy also includes photos, postcards, insignia and even a Gurkha kukri taken from the enemy. This is where we really must mention the editorial work of Philipp Cross, who punctuates the text with background information and musings inspired by his lifetime fascination with his family's (and most especially his great-great-grandfather's) richly documented past. Where the deaths of named individuals come up in the text, he goes above and beyond expectation in not only identifying them but also locating and photographing their graves. His efforts extend even further with the enemy souvenirs, which he has painstakingly connected to specific units and individuals. This is quite remarkable in the case of a handwritten report in Nepalese dialect, and still more so in the case of one Pte. Percy Walsh of 1st Loyal North Lancashires. Philipp Cross not only uncovers Percy's life story but also his living relatives in Blackburn, a fascinating and deeply touching digression which truly exemplifies the author's very personal and emotional approach to his subject matter - quite different from that of his great-great-grandfather and complementary to it.

In summary this volume is a true labour of love which is warmly and enthusiastically recommended both to the specialist and the non-specialist reader. German specialists may be somewhat dissatisfied with some of the choices made in the translation (such as the rendering of rank titles and military terminology into English with a concomitant loss of some precision, or the use of the civilian term 'holiday' where 'leave' is clearly meant), but will probably have already decided to purchase the upcoming German edition instead. Beyond this, it is hard to find fault with the book. I look forward eagerly to reading of Alexander's further experiences in the Carpathians, in Italy and in the 1918 offensives!

A digression of my own - the Saxon connection!

Alexander's peacetime military service is only briefly addressed in the introduction, but the accompanying photos provide enough clues for the specialist reader to fill in the blanks. It appears that in 1900 at the age of 20, Alexander chose to fulfil his service obligation by signing up as an Einjährig-Freiwilliger (one-year volunteer). This expensive self-financing option with restrictive educational requirements was nevertheless popular with the professional classes, as it allowed them to serve for a shorter period at a time and with a unit of their choosing. It also opened the way for potential qualification as a reserve NCO or - ideally - a reserve officer, with all the social prestige that went with it in Wilhelmine society. Alexander was evidently selected as a suitable NCO and achieved promotion to Vizefeldwebel several years later, by which time he had passed from full-time to part-time service as a reservist. Around the age of 27 (so probably in 1907) he will have passed into the Landwehr, and been transferred from the control of his original unit to that of a geographically-based Landwehr-Bezirkskommando determined by his place of residence - and since this was not in Saxony, he now found himself in the Prussian Army both for peacetime Landwehr exercises and in the event of mobilisation.

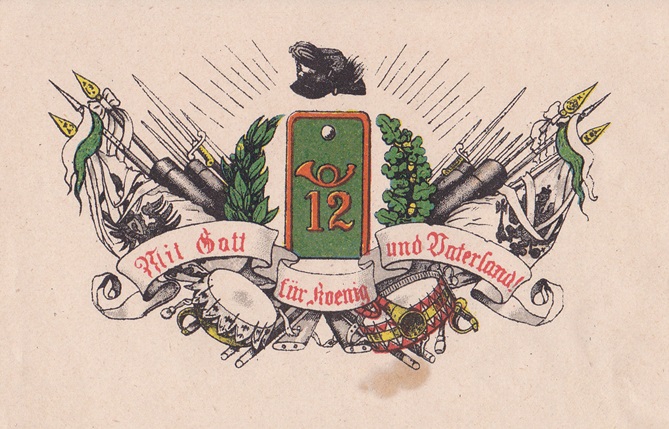

An Einjährig-Freiwilliger could choose any unit which would have him. It is obviously intriguing to us that Alexander chose a Saxon unit - Kgl. Sächs. 1. Jäger-Bataillon Nr. 12 in Freiberg. His home state was the Großherzogtum Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach, the largest of the four intertwined and territorially non-contiguous states ruled by other branches of the Saxon royal house of Wettin and collectively known as the 'Ernestine Duchies'. More specifically however Alexander - like my own great-grandmother's family - hailed from the Neustadter Kreis, an area on the Saxon border which had been ceded by the defeated Kingdom of Saxony to the Grand Duchy in 1815 (alongside much more substantial territorial losses to Prussia!).

This region clearly maintained especially strong economic, cultural and often familial ties to its much larger neighbour, which would only have grown stronger once German unification made the smaller states even less relevant and weakened whatever degree of local patriotism they had commanded. Since only the four kingdoms maintained any military sovereignty within the Reich, Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach even lacked armed forces of its own - though its traditions were maintained by the locally recruited IR 94 of the Prussian Army, with which the (reputedly unpopular) Grand Duke had a solely ceremonial role. It is thus hardly surprising that a young volunteer from the Grand Duchy (or indeed, any of the smaller Thuringian states) would be open to serving a little further from home in the Saxon Army - especially since its reputedly more liberal culture might appear more welcoming to the educated middle class. More superficially the Saxon Jägers possessed both a uniquely dashing uniform (unlike that of any other German contingent) and significant prestige. According to himself Alexander was no oddity - he claims that "almost a third" of the Landwehr men at the Ersatz-Abteilung / JB 11 (which recruited from the whole XI. Armeekorps district) in mid-August 1914 were "former Saxon Jägers, with several having in fact served with me in Freiberg".

Having spent his active and reserve service with the Saxon Army, some of his complaints about his superiors in 1914 may reflect a culture clash with Prussian institutional norms. On 20th November he complains that "our active [i.e. career] officers are very unpleasant with very few exceptions. I haven't yet noticed a hint of the camaraderie between officers and men that is always talked about in the newspapers. On the contrary, there is an indescribably rude tone". With characteristic generosity he immediately names his current company commander (Ltn. Müller, a tellingly non-aristocratic name!) as an exception to this rule, and goes on to praise the pleasantness of the reserve officers - many of whom will have certainly come from similar professional class backgrounds to himself.

This appears to echo the observations of Oberst Freiherr von Uslar-Gleichen in the published history of Kgl. Sächs. 2. Jäger-Bataillon Nr. 13, when describing the battalion's experiences as part of a Saxon Jäger-Regiment within a Prussian division:

"The position of the subordinate in relation to the superior - at all ranks - was freer. Only to the superficial eye did discipline appear to be looser. It was just as tight here [in the Saxon Army] as there [in the Prussian Army]. But the wider possibility of bringing one's own views, plans, perceptions and concerns before the ear of the leader protected the leadership from the danger, not always avoided in war, of seeing things according to one's own wishes instead of according to reality."

I am grateful to Phillip Cross (and to Alexander Pfeifer) for prompting me to investigate this especially interesting angle. I would likewise be grateful to readers for any tips on further primary sources which shed light on the subtle differences between the Saxon Army and the other German contingents.