Prof. Dr. phil. Alexander Pache, also known as Alfred was born on 31st December 1878 in Steinigtwolmsdorf near Bautzen. We do not know which was his first and which his second name, but are certain that both names refer to the same man. He pursued an academic career and by 1914 had achieved the status of Gymnasialoberlehrer (senior secondary school teacher) and published at least two of what would eventually be many scholarly volumes on German literature and history.

Like many such professionals in imperial Germany he was also a reserve officer, (Leutnant der Reserve) and at mobilisation became a platoon commander in Kgl. Sächs. 16. Infanterie-Regiment Nr.182, Germany's youngest peacetime infantry regiment. Formed in October 1912 and garrisoned at Freiberg, it fought in 1914 with 23. Infanterie-Division / XII. Armeekorps on the Marne and subsequently held the line north of Reims.

When 23.ID was reduced to one infantry brigade of three regiments in March 1915, IR 182 joined the likewise 'surplus' IR 178 (from 32.ID) and RIR 106 (from 24.RD) as part of the new 123. Infanterie-Division. Initially deployed with XII.AK on the Aisne, 123.ID soon moved to the Lille area in OHL reserve. After briefly holding sectors near Lens and in the Wytschaetebogen (Wytschaete Salient) in June and July it was committed in August to the murderous Souchez sector facing Notre Dame de Lorette and bore the brunt of the French offensive there on 25 September. Within four days IR 182 alone lost 39 officers and 1,250 NCOs and men killed, wounded or missing. Although himself wounded, Pache remained in action and became a company commander on 29 September as replacement for the slain Oltn. von Mücke of 8./182. From 30 September to 14 October his regiment was in Bereitschaft (immediate reserve) at Wingles, where it received large replacement drafts and began rebuilding. It then returned to Wytschaete, initially (like IR 178 and RIR 106) holding exactly the same sector as in July.

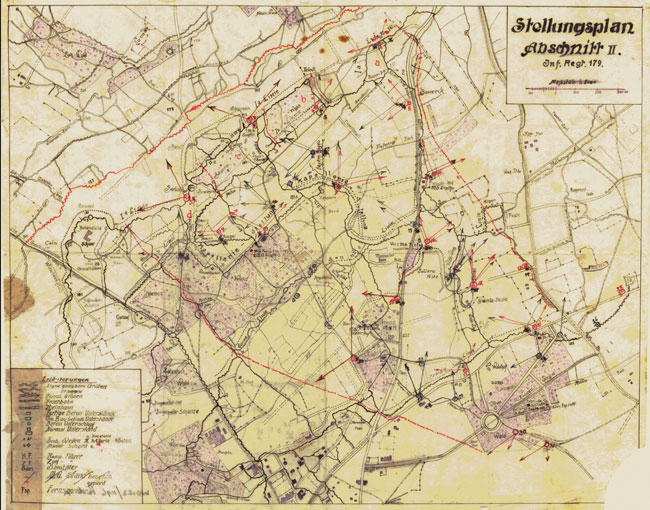

The small wood north of Wytschaete known to Pache as Bayernwald had many names. To the Flemish it was Kroonaard- or Croonaertbos, and accordingly Croonaert Wood to the British. They also knew it as Wood 40, referring like the French Bois Quarante to the height above sea level from which it dominated the terrain to the north and west. The French only ceded this vital ground to 6. Kgl. Bayer. Reserve-Division on 16 November 1914 after many days of hard fighting. In honour of the Bavarians the former Beilwald (Axe Wood) became Bayernwald on German maps. In 1915 it extended much further than today, not only towards St. Eloi but also into part of the field opposite the current entrance. Here lay the front line, plagued from the outset by sloping ground, high groundwater and flanking artillery fire directed from the Kemmelberg (Mont Kemmel). It was supported on either flank by German positions at Hollandsche Schuur Farm and St. Eloi, both already targeted by British tunnellers and destined for destruction on 7 June 1917. In the winter of 1915-1916 however the greatest concern for the Saxons was the rising water level which collapsed trenches and rendered parts of Bayernwald uninhabitable. As a result the Prussians who followed them began work in summer 1916 on a new, deeper trench system behind and uphill of the old line - which it then replaced as the main position from February 1917. The current reconstructed Bayernwald trenches represent only a small part of this newer trench line.

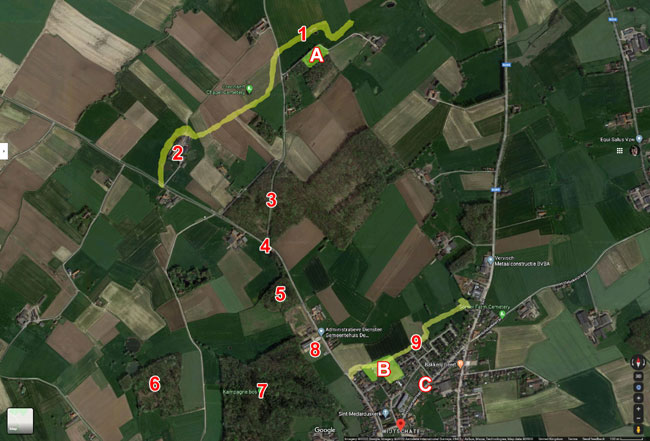

Above: Wytschaete as it appears in Google Maps.

1916 locations:

- Approximate front line in winter 1915-1916.

- Hollandsche Schuur Farm (destroyed by mines at the Battle of Messines on 7th June 1917).

- Hessenwald (Grand Bois).

- Rote Villa (Red Chateau), a ruin which housed a Bataillonsgefechtsstand (battalion battle HQ).

- Zahnstocherwald (Unnamed Wood).

- Markwald (Petit Bois).

- Wytschaeterwald (Bois de Wijtschate).

- The Hospice, described by Pache in the regimental history as “a bulky, red brick building in gothic style, which had still been quite well preserved in July [1915] but was now [in October] badly shot-up and would turn into a pile of rubble over the course of the winter".

- The Sachsengraben, part of the third defensive line on the edge of Wytschaete.

Current locations:

- The excavated and restored Bayernwald trenches.

- Hill 80 dig site.

- The recently rediscovered Kortestollen.

For King and Kaiser includes a whole chapter of Pache's letters home from the Wytschaete salient, previously published only in Saxon veterans' newspapers in the early 1930s and (to our knowledge) never previously translated into English.

The following is an excerpt from one of these letters, addressed from the trenches at Wytschaete. It is dated 28th January 1916, only a day after the events it describes.

...In the afternoon the enemy artillery suddenly opened a half-hour's drumfire on the second trench in our reserve line. We hadn't heard such a racket since Souchez. Luckily my detachment was spared. Only a couple of heavy shells and shrapnel pots went onto the second line of our position. However they did drive us out of the dugout, which rang in all its brand-new joints at every distant or close impact. Outside we observed how the howling masses of iron went over us toward Wytschaete, the Rote Villa, the Zahnstocherwald and the Sachsengraben. Then suddenly a huge flame arose among the shot-denuded spruce trunks of the so-called 'Zahnstocherwald' ['Toothpick Wood'] (the name very aptly describes the state of the remaining trees) and dense smoke welled skyward. A dugout was burning. It was the company commander's dugout in the so-called Bereitstellung [immediate reserve position] Every two weeks I too am there for six days together with batmen and orderlies. When the artillery duel had died down somewhat, I sent my orderlies up there and allowed myself to make enquiries. Meanwhile the commander of the company there, Rittmeister C, was already being sought after by telephone throughout the regimental sector. He had first been transferred to our regiment after Souchez. Around evening it became a tragic certainty, that along with his batman and orderly he had been burned and buried in the dugout. It was only today that the three bodies could be excavated.

Before the world war 'death on the field of battle' was for every man surely an occurrence more or less enveloped in poetry - but in reality it is for the most part so heavily accompanied by terrible, even sickening details, that one understands why poetry must subsequently exert its mitigating, transfiguring effect, if man is at least to be able to bear it in memory. Nothing is so unpoetic, so gruesomely prosaic as such a death - therefore poetry must come and elevate it into the sphere of the high and the beautiful, out of the realms of filth, stench and loathsome hardship! -

You wouldn't believe what an effect the sight of the first snowdrop has after such an experience! I found it blooming in the ruined and overgrown garden of the so-called Einödhof, which lies in the meadow right behind our trench. And the day before I had heard the first starling singing on the barren, shattered stumps of the 'Zahnstocherwald'! A starling, a snowdrop! When one sees dear and diligent men die in such a terrible and needlessly gruesome way, one may doubt God's goodness - but the first twittering of birds, the first shy bloom of the coming spring lets us fervently believe in it again!

As my wife has pointed out, the snowdrops and the return of migrating starlings at the end of January would have been among the very first signs of the change of season. It is striking that even after a second winter at war, major battles and the deaths of many colleagues (among them no doubt many friends) Pache seems to have sincerely retained the instincts and aesthetic ideals of a Romantic poet. Though we know of no poetry written by Pache, his earliest known publication (1904) is a study on nature symbolism in the work of Heine.

The profoundly unfortunate Rittmeister C is identified in Pache's regimental history as Rittmeister d.R. Theodor Walter Coccius, born in Leipzig on 13th October 1878. This recently promoted ex-cavalry officer from Saxon Ulanen-Regiment 17 had been commander of 6./182 since 27th October 1915. Pache had therefore known and worked with Coccius for at least three months. Pache's regimental history records the latter's death as follows: "On 27th February [1916] for the Kaiser's birthday from 4 to 6pm heavy bursts of artillery fire across the entire sector; in course of which Rittm. d.R. Coccius, Kompagniefuhrer [acting company commander] 6.[/182], fell in his dugout together with two orderlies."

Only two other men of 6./182 are reported as killed in the same Verlusteliste (dated 18th February 1916), and are presumably the orderlies - Gefreiter Bruno Fuchs (from Börnichen) and Soldat Kurt Richter (from Reichenbach).

123.ID was relieved by Prussian 46.RD (XXIII.RK) in mid-March 1916. After an extended period in Flanders as a labour force and piecemeal relief for Prussian units in line, the entire division was committed to the Battle of the Somme on 7th July. Having survived being buried alive under British bombardment, Pache would later be awarded the Saxon Ritterkreuz des Militär-St.-Heinrichs-Ordens (the oldest German and highest Saxon gallantry award) for his performance as company commander:

Together with his company Ltn. Pache distinguished himself in the battle of the Somme by outstanding courage in the fierce, bloody fighting for the possession of Trônes Wood in the sector of 12. Reserve-Division during the days 10 to 16 July 1916. After II. Batl. / Inf.-Regt. 182 had taken the wood in a magnificent assault on 9 July, it had to repel an extremely strong English counterattack which was pressed home following the strongest drumfire. The Englishmen who broke into the wood were thrown out again by Ltn. Pache after heavy, dogged single combat. Numerous prisoners were taken and the entire position held. It is only thanks to the valiant conduct of him and his men, his vigilance and initiative, that this attack too - driven home by the English northwest of Combles with superior forces - entirely failed.

The battered 123.ID was transferred to the Eastern Front at the beginning of August 1916. On 6th September IR 182 was permanently detached and transferred to the new Prussian 216.ID, with which it subsequently fought in Galicia as part of the mixed German / Austro-Hungarian / Ottoman Südarmee. In November Pache's regiment travelled to Transylvania and fought the Romanians in the Battle of the Olt Valley. Pache was seriously wounded. Remaining on the Romanian front, IR 182 was again transferred from 216.ID to the henceforth wholly Saxon 212.ID in August 1917. Pache had now been promoted to Oberleutnant and returned to duty, but would see no further fighting on any serious scale.

In May 1918, the entire 212.ID was shipped across the Black Sea to support the German-backed Ukrainian government. The Saxon infantry subsequently spent much time in the countryside around Odessa and Mykolaiv, fighting Makhnovist (Ukrainian peasant anarchist) bands and helping to organise the local Mennonite villagers for self-defense against these raiders. IR 182 (by now perhaps the most widely travelled regiment of the Royal Saxon Army) had the good fortune to be transported home by the end of the year and demobilised, while other units of 212.ID found themselves stuck in Ukraine in a political vacuum after the armistice. The last of them were shipped home from Odessa by the French and Greeks in March 1919. The energetic and articulate Pache was highly active in the IR 182 veterans' association, and his letters from the Somme appeared in its published history (for which he also served as the main author) in 1924. His letters from the Wytschaete salient were serialised in the 1930s by the Saxon veterans' newsletter Der Feldkamerad.

Unknown to us at the time of writing the new book, this highly decorated and courageous officer tragically died on 7th December 1943 as an inmate at Buchenwald Concentration Camp. According to camp records discovered by my wife Diana Zachau, the 64-year-old Pache died of "akute Kreislaufschwäche" (acute weakness of the blood circulation). This vague and popular diagnosis suggests death from overwork, exhaustion and hunger. How, where and when he fell foul of the Nazi state is currently unclear.