Alfred von Heygendorff was born at Bad Elster on 1 March 1868 into minor nobility. His great-grandmother was the distinguished tragedienne and opera singer Karoline Jagemann, who had been granted her estate and title of Freifrau von Heygendorff as mistress to his great-grandfather Carl August, reigning duke (herzog, from 1815 grossherzog) of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach. Like its neighbour Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (famously the home of Queen Victoria's consort Prince Albert) this small Thuringian duchy was ruled by a branch of the Ernestine line of the royal house of Wettin. The rival (and originally junior) Albertine line provided the electors and (from 1806) kings of Saxony, to whom the von Heygendorffs are thus also related.

Alfred's grandfather Karl pursued a career in the Royal Saxon Army and settled in Dresden, ultimately reaching the rank of Generalmajor and retiring before the wars of 1866-71. Alfred's father Bernhard and uncle Alfred both followed Karl into Saxon military service. Bernhard ended his career as an Oberst of Gendarmerie (police) and died peacefully in 1916.

Thus the young Alfred von Heygendorff was destined to be an officer, and would be the first (but by no means the last) of his name to serve in war. From the age of six he was privately tutored at home, and accepted into the prestigious Königliche Gymnasium in Dresden at the age of ten in 1878. After several years of further study at the Großherzogliche Gymnasium in Weimar, Alfred received his Abitur (graduation certificate) and joined Kgl. Sächs. 1. (Leib-)Grenadier-Regiment Nr.100 (LGR 100 - the Saxon infantry life guards) as a Fahnenjunker in March 1887. He received his officer's commission as a Leutnant the following year.

From 1892 to 1894 he was seconded to the Kgl. Sächs. Kadettenkorps, a jealously guarded bastion of Saxon military particularism regarded with considerable suspicion by the Prussian chauvinist press (not least for the presence of many Hannoverian military families who refused to serve directly under the Prussians). While serving there - presumably as an instructor - he was promoted to Oberleutnant in 1893. In May 1894 Alfred married Elsa von Wittern, herself daughter of a Saxon Oberst. They settled in Dresden, producing a daughter (Wera) and two sons (Egon and Ralph) - both of whom in turn became officers with LGR 100.

Evidently Alfred was held in high esteem and personal trust by the Saxon royal family, for from 1898 he served for three years as personal adjutant to Prince Friedrich August, son of King Albert's brother Prince Georg. In June 1902 Albert died childless and was succeeded by Georg, making Friedrich August the crown prince. Following the death of King Georg in October 1904, his son then succeeded him as King Friedrich August III - and Alfred von Heygendorff found himself a friend of the reigning monarch.

At the end of his royal adjutant's appointment in 1901 Alfred was assigned to Kgl. Sächs. 2. Grenadier-Regiment Kaiser Wilhelm, König von Preußen Nr. 101 (GR 101) as a company commander and promoted to Hauptmann. He reached his final pre-war rank in 1911 as Major on the regimental staff. In 1913 he was appointed as a battalion commander in the likewise Dresden-based Kgl. Sächs. 12. Infanterie-Regiment Nr.177 (IR 177 - part of 32. Infanterie-Division), with which he went to war the following summer.

While lying in the firing line with his men at Perthes in the Champagne on 1st September 1914, Major von Heygendorff was wounded by a shrapnel ball and had to cede command of the battalion, but insisted on remaining with IR 177 in the field. Due to heavy officer losses he reported fit for duty again a few days later, although his wound was not healed and had to be freshly bandaged every day. On 2nd October he was given acting command of Kgl. Sächs. 13. Infanterie-Regiment Nr.178 (IR 178 - part of 23. Infanterie-Division), which was down to a strength of two companies. The regiment was refilled with replacements a few days later and Alfred appointed as one of its battalion commanders. On 22nd October he was awarded the Iron Cross 1st Class.

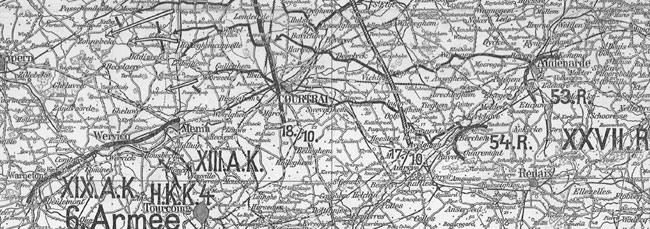

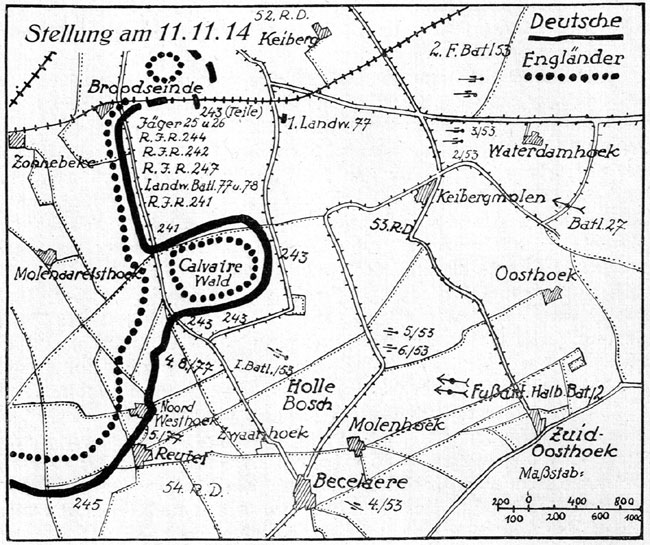

The following day Major von Heygendorff was sent to take over Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr.245 with 54. Reserve-Division of the Saxon-Württemberg XXVII. Reserve-Korps, then heavily engaged in the First Battle of Ypres.

His exemplary and energetic leadership of this undertrained and demoralised volunteer regiment in truly appalling circumstances earned him the Ritterkreuz of the Militär-St.Heinrichs-Orden (the highest Saxon and oldest German gallantry order) on 17th November.

Without exception the surviving writings of his officers and men describe him with great affection, often calling him the 'soul of the regiment'. This was magnified after his death when he became a symbol of the regiment's sacrifice on the Somme, much commemorated in regimental postcards and in the veterans' newsletter Was wir erlebten – 245er Erinnerungen ('What We Experienced - Memories of the 245ers'). In a 1922 issue, Professor Max Geissler of Leipzig wrote:

Rarely indeed has a regimental commander been able to describe his regiment as 'his' in such a strict sense as he could. Rarely indeed have those belonging to a regiment regarded their commander as 'theirs' in such a heartfelt sense [as we could].

As the division's senior regimental commander Major von Heygendorff was also well regarded by his superiors. During the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915 he was entrusted by 54.RD with a critical role, as recounted in detail in For King and Kaiser . Considering the well-documented mutual distrust and antagonism which all too often arose between the Saxon and Württemberg elements of XXVII.RK, it is particularly remarkable that on this occasion he exercised direct command of Württemberg troops for two weeks. So far as we can tell from a survey of their (often frank and opinionated) literature, none of his Württemberg peers had a bad word for the Saxon commander of RIR 245.

While the XXVII. Reservekorps and attached units continued to hold the eastern end of the Ypres salient from Polygon Wood to Passchendaele, a task force of corps reserves including Major von Heygendorff's composite regiment (composed of a battalion each from RIR 245, 246 and 247) took part from 24th April in the offensive against the northern face of the salient. Driving southward toward Zonnebeke, 'Regiment von Heygendorff' took numerous British and Canadian prisoners before the enemy abandoned the tip of the salient under cover of night on 3rd-4th May 1915. The composite regiment was then disbanded and its triumphant Major commander took charge of RIR 245 again during the subsequent advance which took them as far as Verlorenhoek.

Subsequently promoted to Oberstleutnant, von Heygendorff's luck finally ran out when XXVII.RK was committed to the Battle of the Somme in September 1916. On 9th September his older son Egon (the regimental orderly officer of RIR 245) was severely wounded by artillery fire on the steps of his HQ cellar in Rancourt. Egon died the next day at hospital in Manancourt, and his father's last letter home was to break the news to his mother. On 12th September, as the published history of RIR 245 states:

At 7.15 pm a heavy shell smashed through the vault of the underground observation post and buried the entire regimental staff. Rescue efforts began at once, but only managed to recover the body of the revered commander an hour later. With Oberstleutnant von Heygendorff fell his adjutant Leutnant Müller, the commander of the MGK Leutnant Ramshorn, Leutnant Fischer-Brill and many brave runners.

Alfred von Heygendorff's younger son, Ralph, survived both world wars with the final rank of Generalleutnant in the Wehrmacht and died in 1953.

Extracts from von Heygendorff's private diary were later provided by his widow and surviving son to the regimental veterans' association and serialised in 'Was wir erlebten'. Written at the time and seemingly neither edited nor intended for publication, these entries provide a shockingly frank and immediate account of the chaotic situation he faced upon taking command of RIR 245.

On 20th October 1914 the regiment had stormed the village of Becelaere (Beselare) alongside Württemberg RIR 246, but rapidly became bogged down in costly attempts to take the British positions beyond (toward Polygon Wood). Cohesion was lost, and the intermingled German units in Becelaere suffered severely from British and misdirected German artillery fire. The many casualties included the original commander of RIR 245. Oberst z.D. Karl Artur Baumgarten-Crusius had survived personally leading the assault on the 20th only to be wounded by (purportedly) a German shell on the 21st. Invalided out of service with the honorary (charakterisiert) rank of Generalmajor, he would become one of the most prolific historians of the Royal Saxon Army and co-author of its three-volume quasi-official history Sachsen in Grosser Zeit.

By the time the Kriegsministerium in Dresden had dispatched Major von Heygendorff to assume command of RIR 245 on 23rd October, the regiment had also lost two of its three battalion commanders. Worse still for the 54.RD, its solitary brigade commander Württemberg Genltn. a.D. Karl von Reinhardt had been killed by a stray bullet on the 22nd while visiting the lines of RIR 245.

Above: Although subjected to prolonged and intense attention from British (and sometimes German) artillery during the First Battle of Ypres, the village of Becelaere was still surprisingly intact in 1915. Most of the artillery fire had been shrapnel, ruinous to windows and slates but no threat to the structural integrity of brick buildings.

After its capture by 54. Reserve-Division on 20th October the church (right) was pressed into use as a dressing station. On the 25th several heavy shells penetrated the roof, causing hideous carnage among the helpless stretcher cases crowded inside. Two stretcher-bearers were killed and three wounded during the desperate rescue operation. Vizefeldwebel Erich Kühn of RIR 244, another of our featured diarists in Fighting the Kaiser’s War, was among those whose lives were saved.

24 October

We travel right through the night. There is no thought of sleep. The route goes via Maubeuge and into Belgium between Ostend and Ghent. In Tielt we report to the AOK, where we learn that our Reservekorps - four have been formed - are not advancing due to a lack of active leadership, the dreadful losses taken immediately upon entering the battle and their composition from Landwehr and war volunteers. ...

We proceed to Dadizeele and report to the Generalkommando (General v. Carlowitz). I am appointed regimental commander of RIR 245, belonging to the 54. (Württemb.) Division (Exz. v. Schäfer) and then head off to find my regiment, which has been scattered and engaged in combat since Monday (today is Saturday). In Becelaere I meet the acting brigade commander Oberst v. Roschmann [RIR 246], who briefs me but emphasises the hopelessness of the situation. So now I'm standing here in the town with no troops (they are out in front, I. Batl. is detached), no horses (they are swimming in northern France), no baggage (it was left at the Generalkommando), no nosebag (my orderly has disappeared with it), no billet and no hope. The street is teeming with stragglers from all regiments, who have come out of the trenches to fetch some food (as they have received nothing since Monday) or to bring in the wounded (which they are not authorised to do for themselves). I search them out in the houses and cellars. The complaint is always: we have no leaders and no food. ... Finally I have 1 ½ platoons together and deploy them behind the village, since the place is coming under a great deal of artillery fire.

25 October

The fun lasted until 2am, then I laid down deathly tired on the bed in the brigade guardhouse. Crazy rifle fire during the night. ... The next morning I insist that my II. Batl. (v. Wachsmann) be put back at my disposal, so that I can relieve the forward firing line and get my sub-units in order. Around midday the regimental adjutant Ltn. Bachmann and battalion adjutant Ltn. Wienicke turn up, having spent three days stuck in a house with the English lying only 30 metres away. They managed to sneak past. I gather that the [previous] regimental commander Oberst Baumgarten [-Crusius] is wounded, the battalion commander Oberstltn. Haeser [I./245] has fallen and Oberst Hesse [III./245] is wounded. As v. Wachsmann [II./245] and his officers are receiving orders from me, a shell strikes the house. Splinters fly everywhere. And now a bombardment is let loose which beggars all description. There are surely spies there who have betrayed our position, as the most frenzied fire is directed at the staff quarters. I have destroyed a telephone line, had a windmill burned and cut the guyropes of a factory with wind catchers which struck me as suspicious. Naturally we relocate. About 5pm I receive an order to advance with my 'reserves' as protection for the artillery deployed to our north, because the 53. Reserve-Division fighting on our right is retreating from an English breakthrough. Thank God our heavy artillery shoots exceptionally well and commits no fratricide. The breakthrough fails. I would have been unable to do anything about it, since I have only found about 30 men. I go back home. The relief takes place. Around 1am I have the I. and III. Batl. together, in total 350 men! Major Franz has also been sent to me – now despite it all there is some sort of order. Torrential rain.

Above: One of these two corporals (we do not know which) photographed at Zeithain before the regiment’s departure for Flanders is Unteroffizier der Landwehr Arthur Bertram of 11. Komp. / RIR 245. Born at Hohenfichte near Flöha, Bertram is recorded as ‘lightly’ wounded in the initial fighting of 21st-24th October 1914.

RIR 245 was officially formed in Leipzig on 25th August 1914, part of a huge wave throughout Germany of new reserve units beyond those allowed for in the mobilisation plans. While a likely majority of the new regiment’s enlisted men were previously untrained supplementary reservists (Ersatz-Reservisten) or young war volunteers (Kriegsfreiwillige), its NCOs were - by necessity - drawn mainly from the older categories of trained reservists. Many of the officers were ‘dug-outs’ from retirement (außer Dienst) or semi-retirement (zur Disposition), including the regimental commander and all three battalion commanders.

Like countless other units of all arms serving with the XXII., XXIII., XXVI. and XXVII. Reservekorps, RIR 245 received a drastically accelerated training program (much hampered by equipment shortages) during September and early October before being rushed with indecent haste into the Flanders offensive. The human cost of this desperate strategic gamble proved to be staggering.